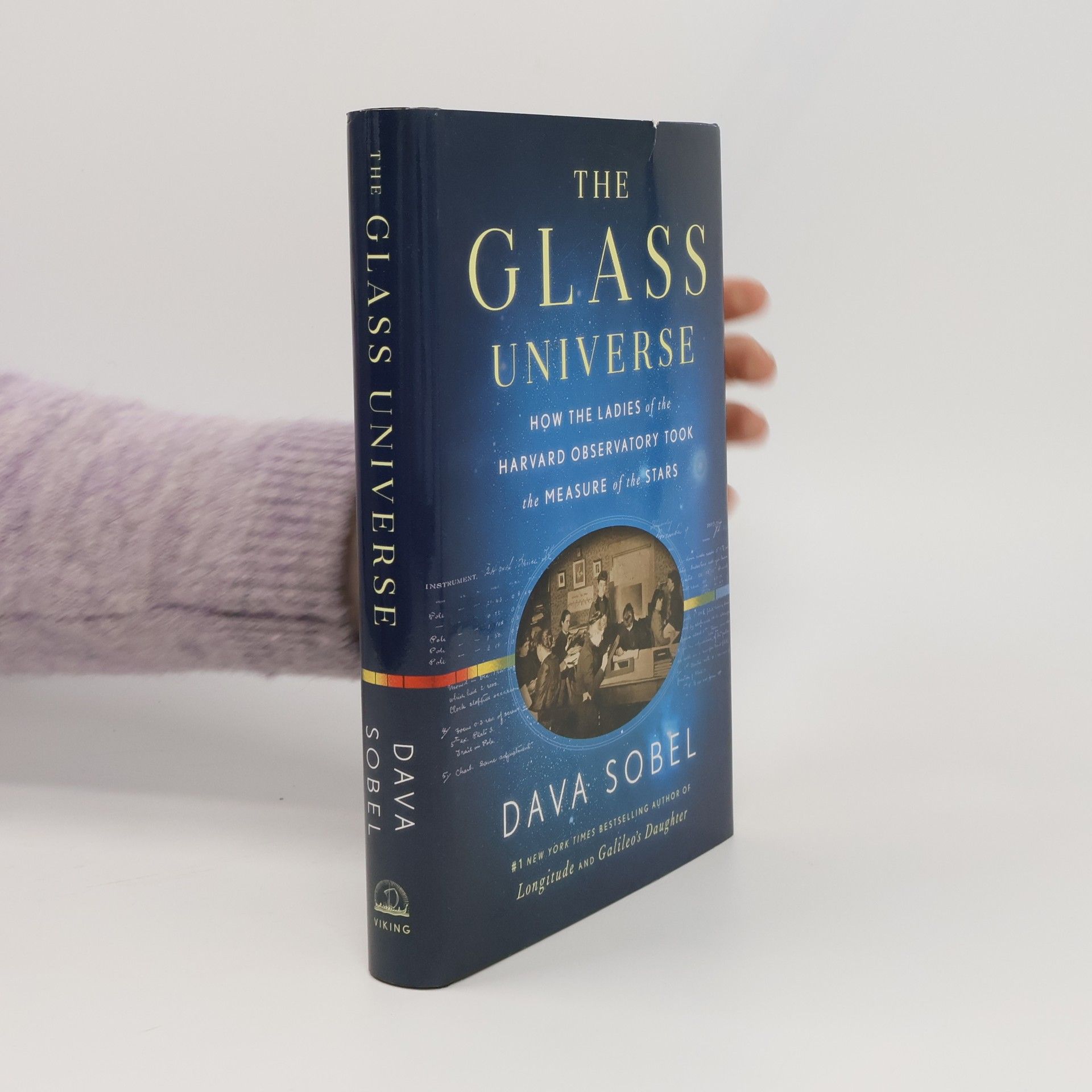

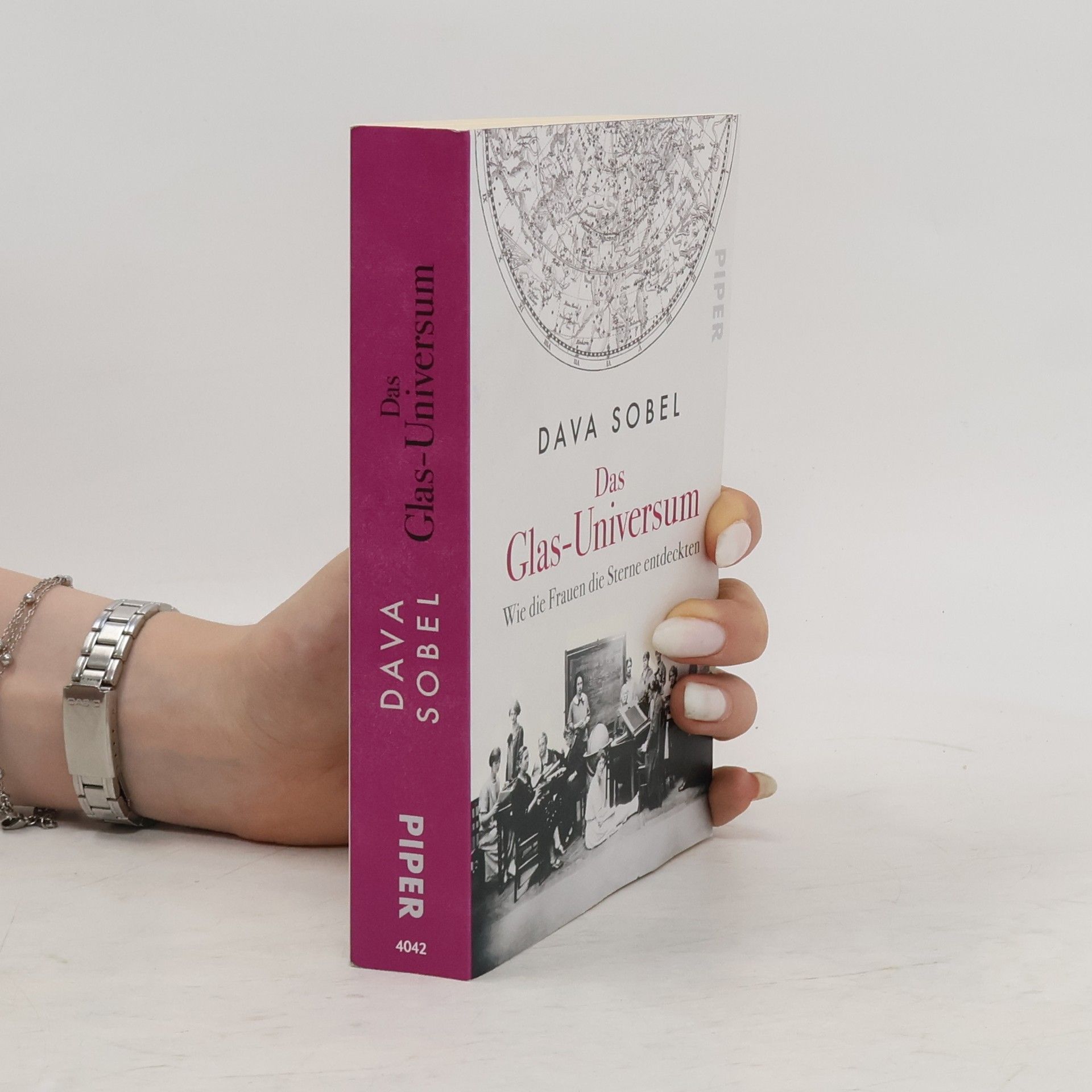

In einer Zeit, als Edison mit seiner elektrischen Glühbirne für Aufsehen sorgte, begannen Frauen an der amerikanischen Ostküste, die Gestirne zu erkunden. In den 1880er-Jahren engagierte ein Professor der Harvard University Frauen als „Computer“ am Observatorium. Dazu gehörten nicht nur Angehörige von Astronomen, sondern auch Absolventinnen neuer Frauen-Colleges und leidenschaftliche Sternbeobachterinnen. Diese Frauen leisteten Erstaunliches: Williamina Fleming, eine ledige Mutter und ehemalige Haushälterin, entdeckte rund 300 Sterne, während Antonia Maury eine eigene Klassifikation der Planeten entwickelte, die als Grundstein der modernen Astrophysik gilt. Dennoch fanden nur wenige von ihnen später die verdiente Anerkennung. Dava Sobel widmet sich in ihrem neuen Buch dem Wirken dieser ambitionierten Wissenschaftlerinnen und setzt ihnen ein Denkmal. Die Autorin hat intensiv recherchiert und präsentiert ihre Erkenntnisse auf spannende und persönliche Weise. Sobels Werk sensibilisiert die Leser für historische Geschlechterungleichheiten in der Wissenschaft und zeigt, dass unser Wissen über den Nachthimmel auf den Verdiensten beider Geschlechter beruht. Es ist ein lebendiges Porträt fast vergessener Wissenschaftlerinnen, die entscheidend zur Entwicklung der Astrophysik beitrugen.

Dava Sobel Bücher

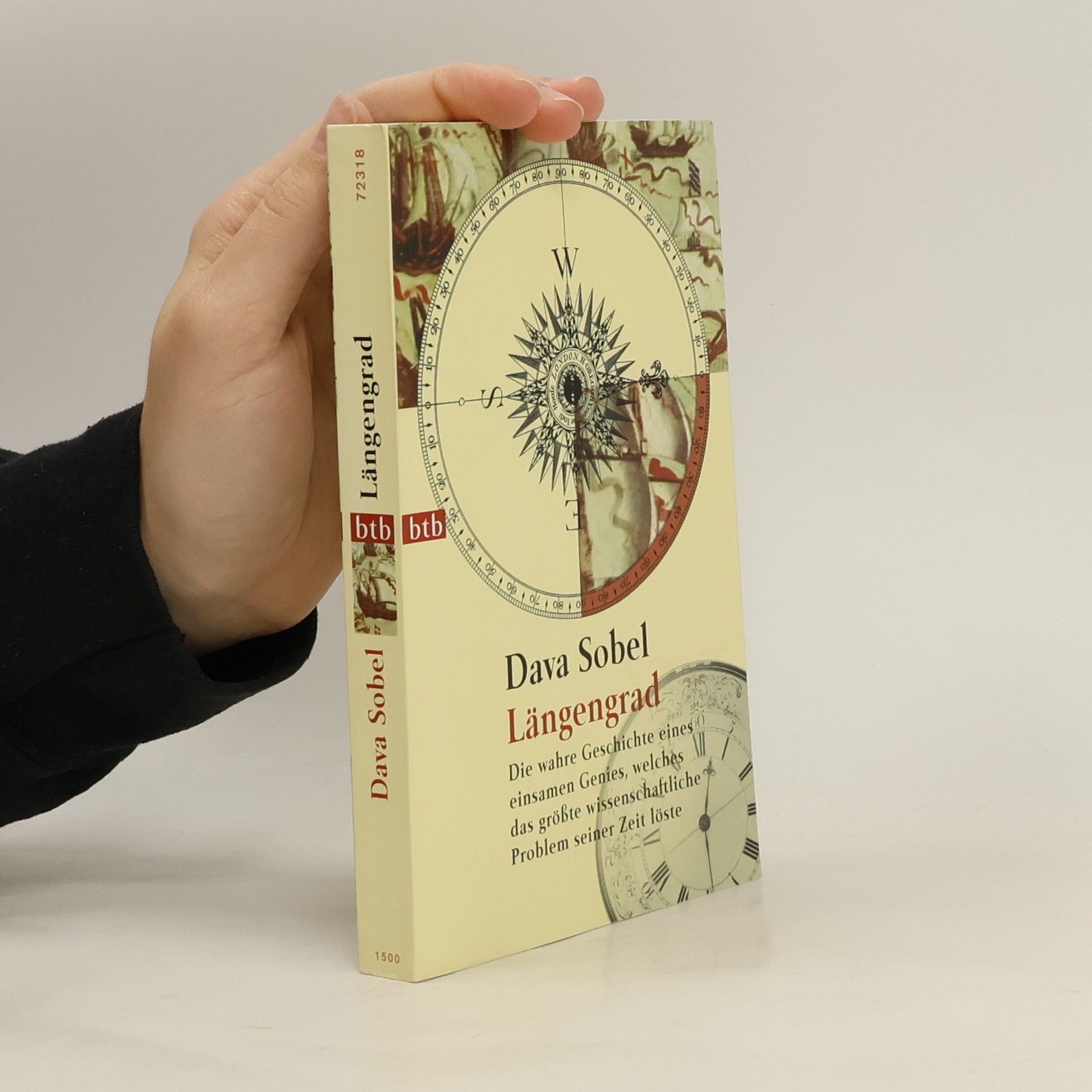

Dava Sobel ist eine anerkannte Autorin populärwissenschaftlicher Darstellungen. In ihrer vier Jahrzehnte umspannenden Karriere als Wissenschaftsjournalistin hat sie für zahlreiche Magazine geschrieben und mehrere Bücher mitverfasst. Ihr bekanntestes Werk befasst sich mit den Komplexitäten der Längen- und Breitengrade.

Längengrad

- 239 Seiten

- 9 Lesestunden

Dava Sobels Längengrad erzählt, wie der Wissenschaftler und Uhrmacher William Harrison im 18. Jahrhundert eines der kompliziertesten Probleme der Geschichte löste: auf See die Ost-West-Position bestimmen zu können. Dieses Buch ergänzt die Geschichte mit vielen Bildern und vermittelt dem Leser damit ein besseres Verständnis für die damalige Zeit, die Akteure und das Problem, das es zu lösen galt. Hier ging es um keine obskure, seltene Schwierigkeit -- ohne Längengrad gerieten die Schiffe oft so weit vom Kurs ab, daß die Seeleute verhungerten oder an Skorbut starben, bevor sie einen Hafen erreichen konnten. Ein von der Regierung initiierter Wettbewerb setzte einen hohen Geldpreis für denjenigen aus, der eine Methode entwickeln würde, den Längengrad genau zu bestimmen. Der Wettlauf begann. Der erbitterterte Kampf um Genauigkeit -- und den stärkeren Willen -- zwischen Harrison und seinem Erzrivalen tobte ohne Rücksicht und es fehlte ihm nicht an Dramatik. Das ist Hollywood-Filmstoff! Längengrad überrascht, fasziniert und gewährt einen Blick in die Vergangenheit bevor Satelliten zur globalen Lagebestimmung alles so einfach aussehen ließen. --Therese Littleton

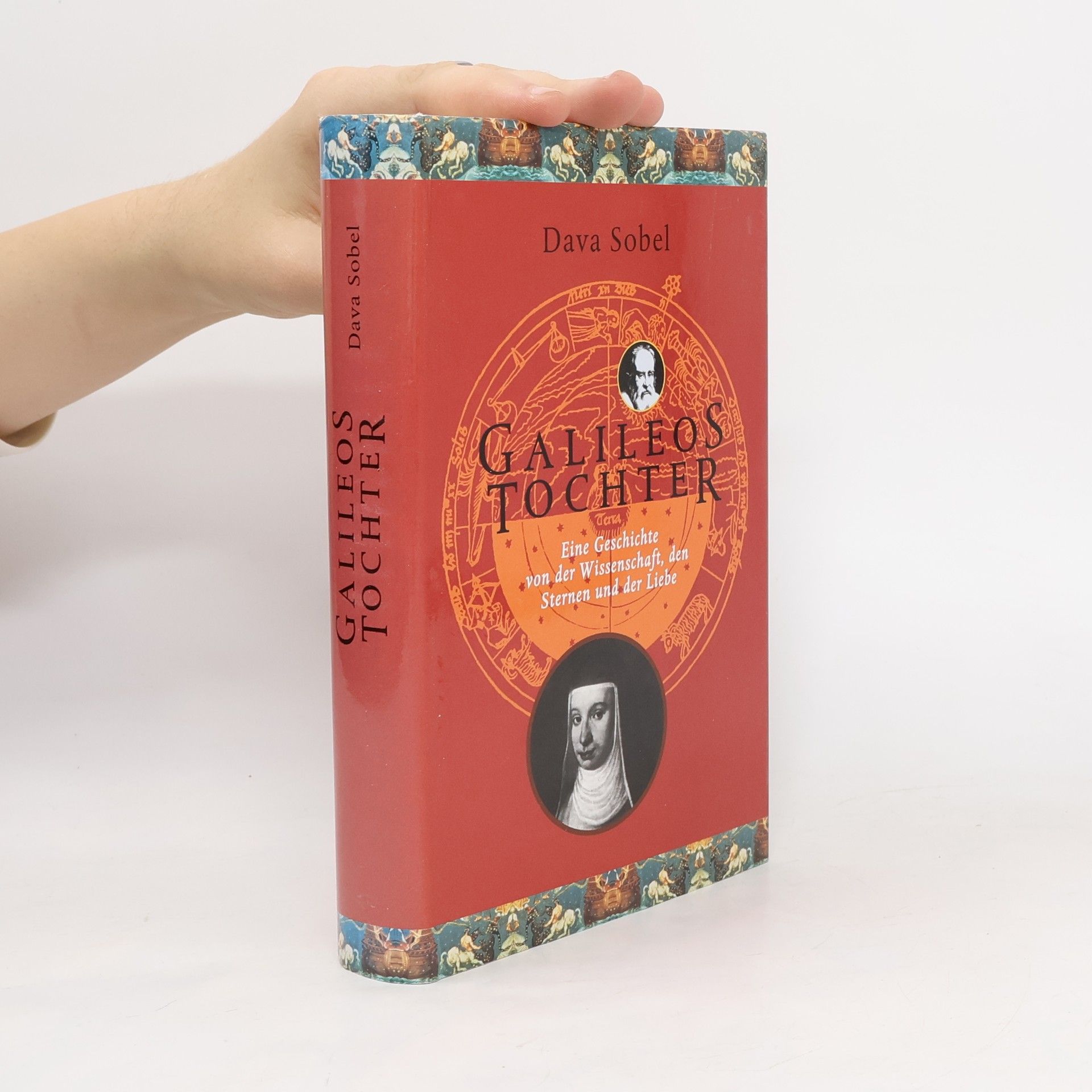

Celeste ging bereits als junges Mädchen ins Kloster. Über hundert Briefe an den Vater sind erhalten und zeigen einen Galileo, wie wir ihn nicht kennen: voller Mut, die Wahrheiten, auf die er stieß, zu erklären. Sobel versteht es meisterlich, die Stimmen von Galileo und seiner Tochter in ihre Erzählung einzuweben. Und sie führt uns die wohl dramatischste Konfrontation von Kirche und Wissenschaft vor Augen, die es in der Geschichte gegeben hat.

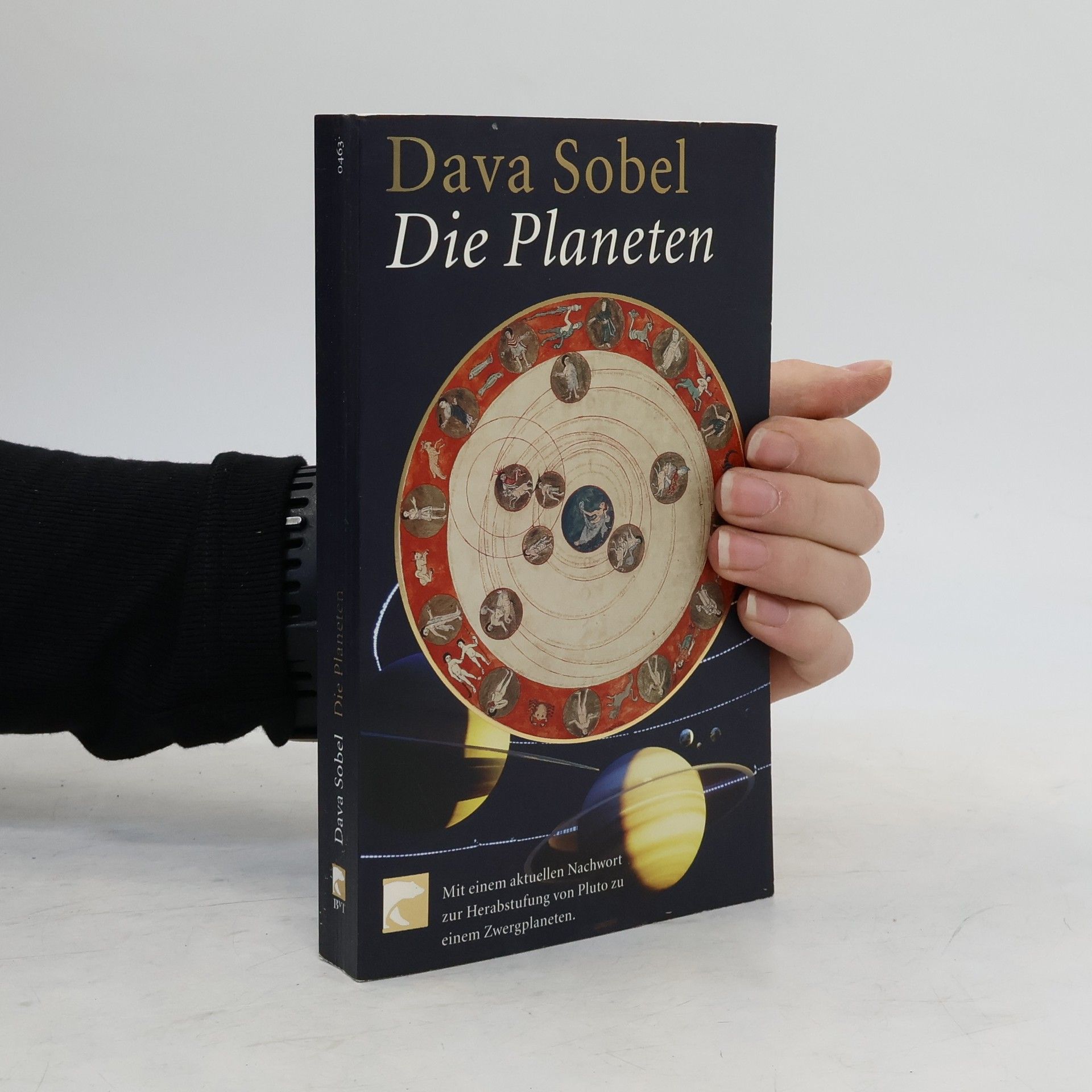

Der Kosmos ist kalt, groß und unbegreifbar? Nicht bei Dava Sobel. Unnachahmlich vermittelt sie Wissenschaft erzählerisch und packend. Wer nach den Sternen fragt, so die Botschaft dieses charmanten und klugen Buches, wird am Ende immer wieder auf der Erde landen. Denn die Geschichte der neun Planeten ist nicht nur die Geschichte ihrer Entdecker, sondern sie erzählt auch davon, wie man den Himmelskörpern seit Menschengedenken eine Bedeutung in Kunst, Mythologie und Literatur zugeschrieben hat. Eine Reise zu den Sternen auf neuen und niemals vermuteten Wegen.

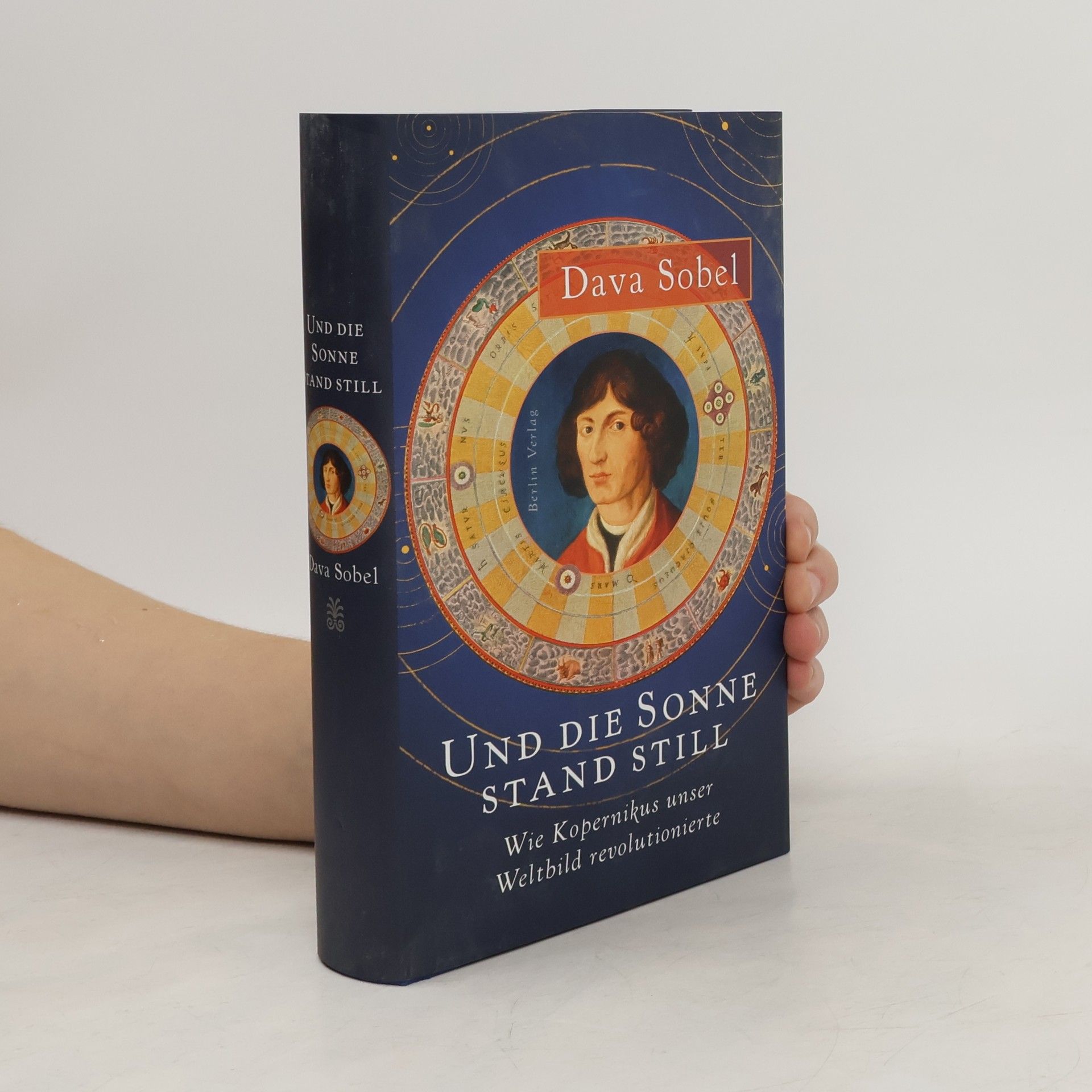

Schon um das Jahr 1514 verfasste Nikolaus Kopernikus eine erste Skizze seiner heliozentrischen Theorie. Nicht die Erde stand demnach im Mittelpunkt des Universums, sondern die Sonne, und die Planeten umkreisten sie. Diese Schrift war revolutionär, aber nur einem kleinen Kreis von Astronomen bekannt. Anhand zahlloser Sternenbeobachtungen entwickelte Kopernikus seine Theorie weiter, das betreffende Manuskript hielt er jedoch unter Verschluss. Die geheimnisumwitterte Existenz dieser Schrift trieb Wissenschaftler in ganz Europa um. Im Jahr 1539 begab sich schließlich der junge deutsche Mathematiker Georg Joachim Rheticus nach Frauenburg, um Kopernikus zu überreden, sein Werk zu veröffentlichen. Unter dem Titel De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (Über die Umschwünge der himmlischen Kreise) sollte das Buch unser Verständnis von unserem Platz im Universum für immer verändern. Elegant erzählt Dava Sobel die Geschichte der Kopernikanischen Revolution und bettet sie ein in die Geschichte der Astronomie von Aristoteles bis zum Mittelalter. Wie schon in ihren Bestsellern Längengrad und Galileos Tochter liefert sie so das unvergessliche Porträt einer wissenschaftlichen Großtat.

Galileos Tochter

Eine Geschichte von der Wissenschaft, den Sternen & der Liebe

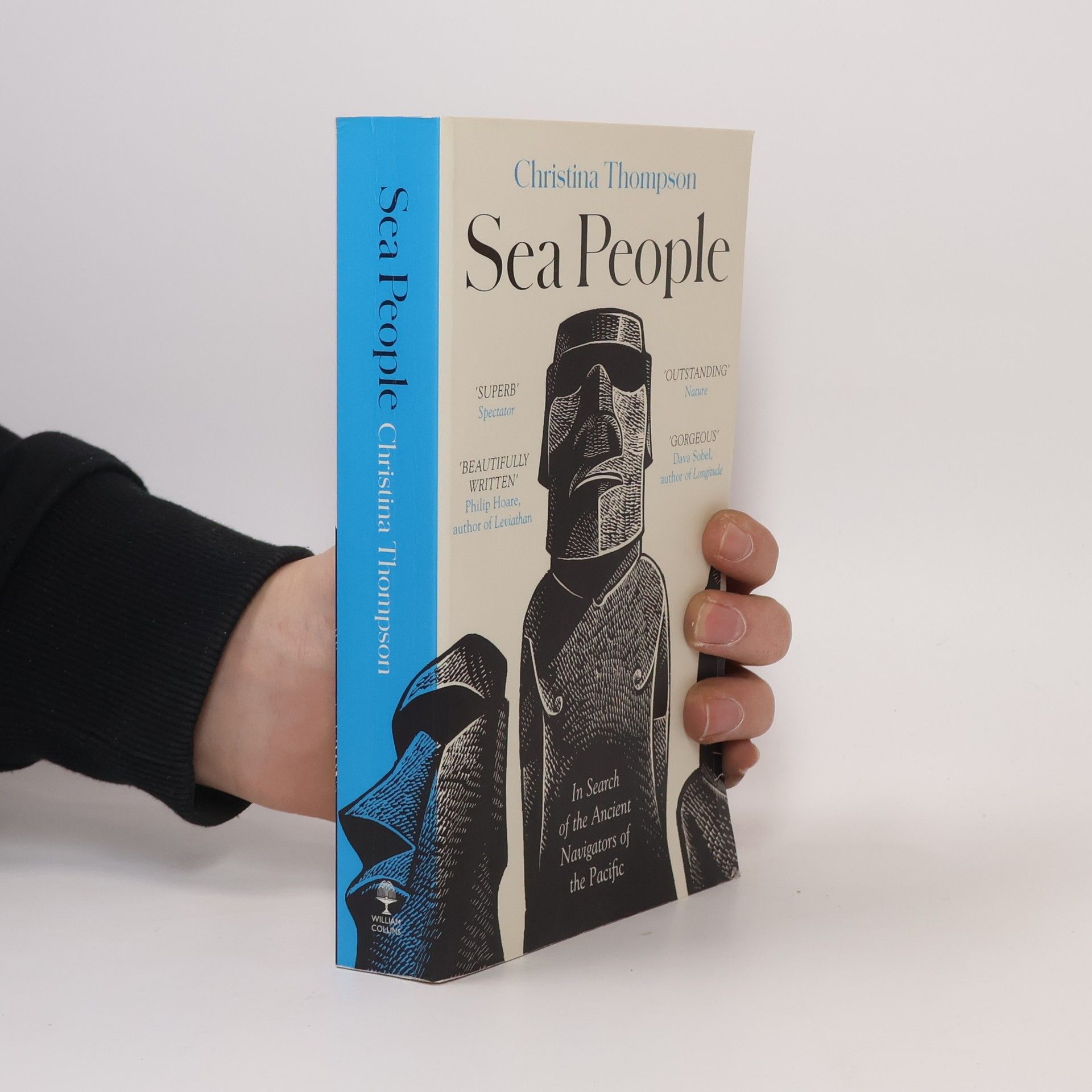

For over a millennium, Polynesians have inhabited the remote islands of the Pacific, a vast triangle from Hawaii to New Zealand to Easter Island. Before European explorers arrived, they were the sole inhabitants of these islands. Polynesians, both closely related and widely dispersed, trace their ancestry to epic voyagers who embarked on remarkable journeys across the ocean. The mystery of how these early Polynesians discovered and colonized such distant islands—without writing or metal tools—has puzzled scholars since the eighteenth century, known as the Problem of Polynesian Origins. This enigma is particularly personal for the author, whose Maori husband and sons descend from these ancient navigators. In this exploration, she delves into the rich history of these ancestors and the contributions of sailors, linguists, archaeologists, folklorists, biologists, and geographers who have sought to understand this legacy for three centuries. Blending history, geography, anthropology, and navigation science, the narrative offers a vivid tour of one of the world’s most intriguing regions, capturing the essence of Polynesian exploration and its significance in human history.

The Glass Universe

- 324 Seiten

- 12 Lesestunden

Named one of the best books of the month by various prestigious outlets, the work showcases Sobel's talent for detail and elegant prose. Critics praise her ability to illuminate the intricate web of individuals who contributed to our understanding of the stars, describing it as a joy to read. The narrative captures both scientific breakthroughs and the personal lives of pioneering women, highlighting how their achievements in astronomy and photography paralleled the progress of female empowerment. Sobel traces a remarkable line in American female achievement, vividly portraying the spirit of these early astronomers who began as 'human computers' at Harvard Observatory. The book serves as an inspiring tribute to these often-overlooked female pioneers and their contributions to science. Reviewers commend Sobel for interweaving professional accomplishments with personal insights, creating a compelling and emotional narrative. The work is described as sensitive, exacting, and filled with the wonder of discovery, showcasing Sobel's extraordinary skill in uncovering hidden stories of science. It is a feast for those eager to learn about resolute American women who expanded human knowledge, presented with grace, clarity, and historical context. Overall, the book is celebrated as a significant contribution to intellectual history and a captivating read.

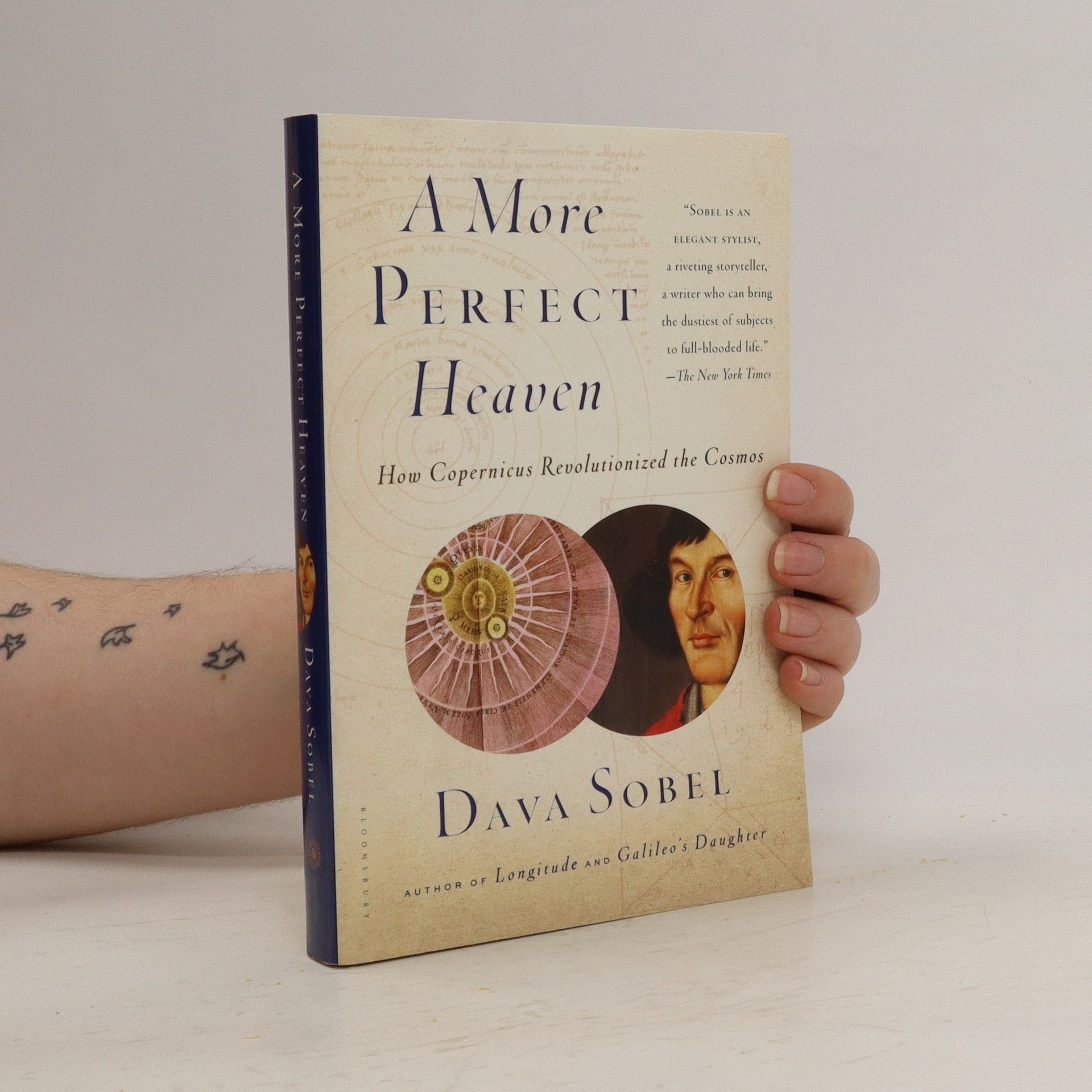

A More Perfect Heaven

- 288 Seiten

- 11 Lesestunden

By 1514, the reclusive cleric Nicolaus Copernicus had developed an initial outline of his heliocentric theory-in which he defied common sense and received wisdom to place the sun, and not the earth, at the center of our universe, and set the earth spinning among the other planets. Over the next two decades, Copernicus expanded his theory and compiled in secret a book-length manuscript that tantalized mathematicians and scientists throughout Europe. For fear of ridicule, he refused to publish. In 1539, a young German mathematician, Georg Joachim Rheticus, drawn by rumors of a revolution to rival the religious upheaval of Martin Luther's Reformation, traveled to Poland to seek out Copernicus. Two years later, the Protestant youth took leave of his aging Catholic mentor and arranged to have Copernicus's manuscript published, in 1543, as De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres)-the book that forever changed humankind's place in the universe. In her elegant, compelling style, Dava Sobel chronicles, as nobody has, the conflicting personalities and extraordinary discoveries that shaped the Copernican Revolution. At the heart of the book is her play "And the Sun Stood Still," imagining Rheticus's struggle to convince Copernicus to let his manuscript see the light of day.

Elements of Marie Curie

How the Glow of Radium Lit a Path for Women in Science

Focusing on the life and contributions of a groundbreaking female scientist, the book explores her significant impact on the field and highlights the lesser-known stories of the young women who trained in her laboratory. Through a blend of biography and historical context, it sheds light on their struggles and achievements, offering a fresh perspective on women's roles in science. The narrative emphasizes both the individual's legacy and the collective experiences of women in a male-dominated profession.