Als Die Blumen des Bösen 1857 in einer Auflage von 1.100 Exemplaren erscheinen, wirkt das Buch wie ein Faustschlag ns kollektive Gesicht des Bildungsbürgertums, das sich die Poesie poetisch wünscht: feierlich, erhaben und gelegentlich galant, etwas für Mußestunden, die den Alltag erhöhen. Und hier besingt einer in bisher unerhörter Formvollendung ausdrücklich den Alltag, den Dreck, das Kranke, die Unterwelt, den Abschaum und die Ausgestoßenen, die Revolte gegen menschliche wie göttliche Ordnung. Denn der Schöpfer hat mit Erschaffung der Welt seine Unschuld verloren; er ist als Seinsgrund auch Urheber des Bösen. Die Schöpfung als Sündenfall Gottes. – Nie zuvor ist derart Unerhörtes Wort geworden. Baudelaire ist der Kirchenvater und sein einziger Gedichtband ist die Offenbarung der Modernen Poesie. Seine Blumen des Bösen haben durch den Dichter Stefan George die bis heute würdigste deutsche Entsprechung gefunden.

Cyril Scott Reihenfolge der Bücher (Chronologisch)

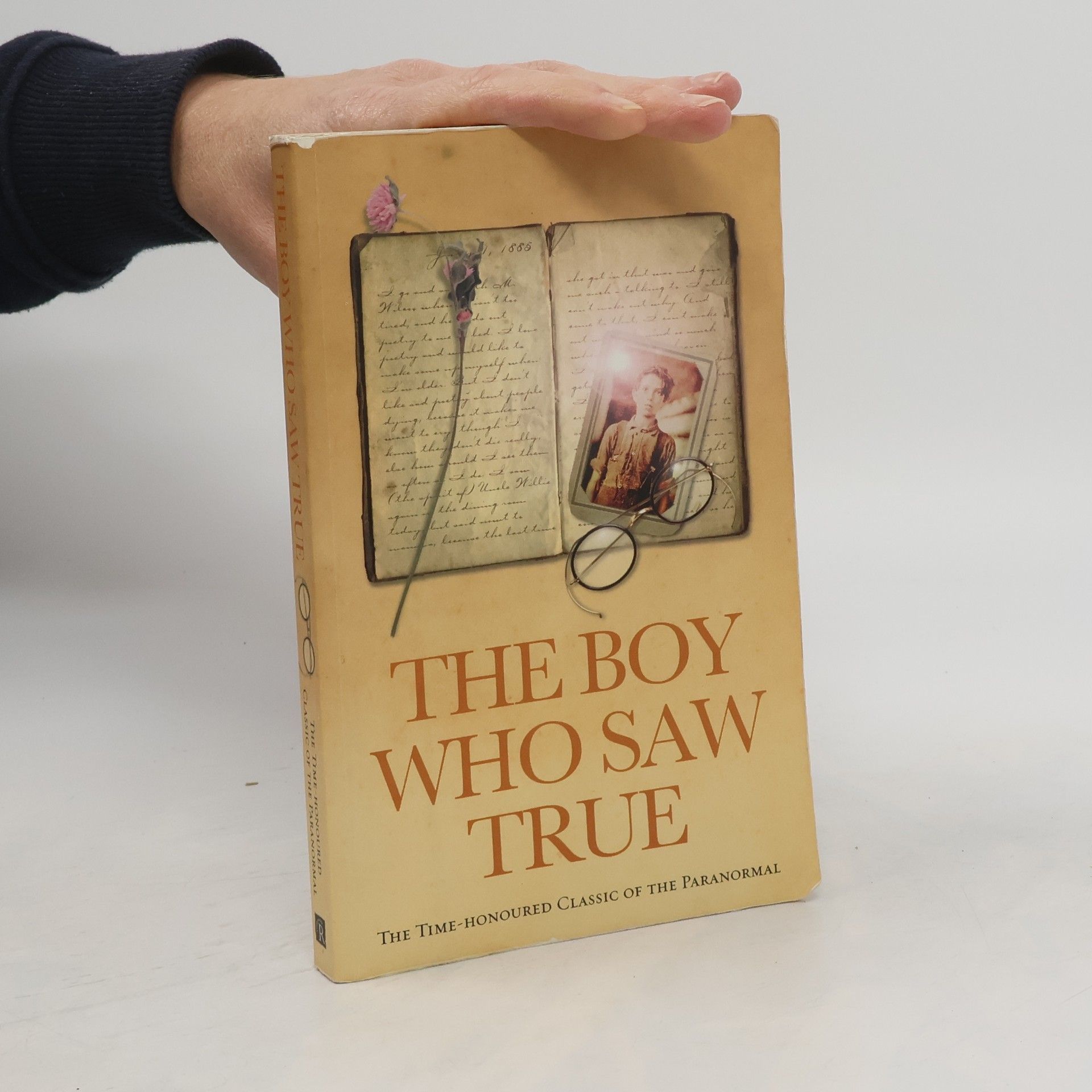

The Boy Who Saw True

- 248 Seiten

- 9 Lesestunden

He asked me if I believed in ghosts.And I said, yes.Then he wanted to know if I'd ever seen one, and I said, lots.'Weren't you afraid?''Not when they're nice ghosts,' said I, 'but I don't like nasty ones ...''The Boy Who Saw True differs from all the hundreds of books I have read on Spiritualism and kindred subjects,' writes the celebrated occultist Cyril Scott in his preface to this remarkable work. 'Not one of them has ever displayed the characteristics of this highly diverting human document, with its naïve candours, its unconscious humour, its oscillations between the ridiculous and the exalted, and its power to convince, for the very reason that the young diarist never set out with the intention of convincing. Here was a precocious young boy born with clairvoyance who could see auras and spirits, yet failed to realise that other people were not similarly gifted.'This is the Victorian diary of a boy whose extraordinary supernatural talent unfurls within these pages. A compelling read, The Boy Who Saw True is a time-honoured classic of the paranormal.

Černý zázrak

Surová černá melasa z cukrové třtiny, zázračná přírodní potravina

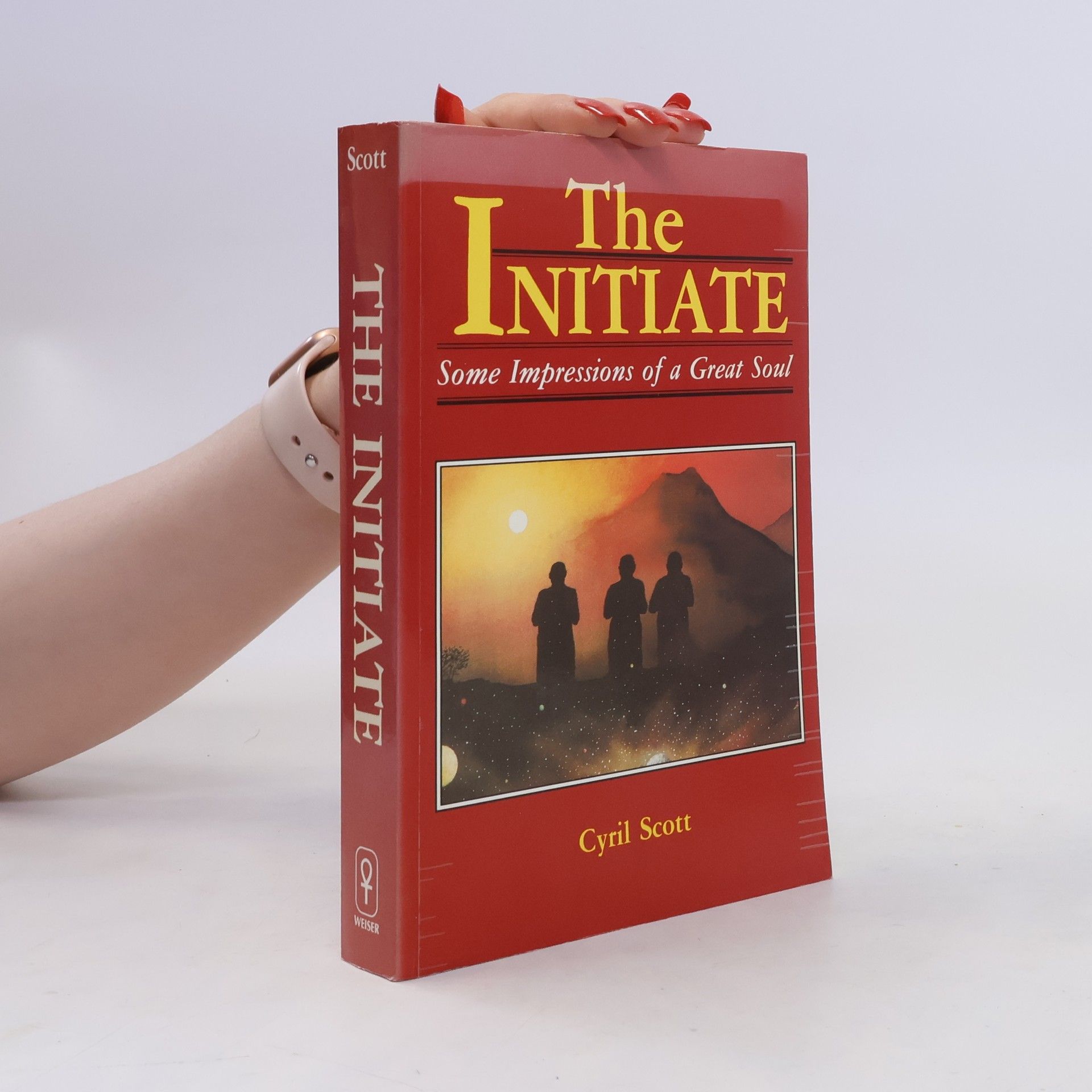

Written as a sequel to The Initiate, the Pupil, as Scott called himself, reconnects with his master, Justin Moreward Haig, after not seeing him for many years. Scott is invited to leave London to stay in Boston, where Justin Moreward Haig is teaching about thirty other students. As in The Initiate, Scott related his experiences as if he were keeping a diary, so that this second book is also a teaching story. For example, the master discusses concentration, meditation, and contemplating, telling the Pupil, let people meditate often but only for short periods of time. It is better to meditate, say, ten times a day for a few moments or even less, than a whole hour in succession. Or, With regard to puritywhat we mean by the word is not prudery but the exact opposite. Purity is the power to see the beautiful in all things and all functions of life, and to glorify all actions by the spirit of unselfishness. As the story unfolds, you will find yourself in the presence of a great teach, who shows you how to attain spiritual consciousness while living an ordinary life.

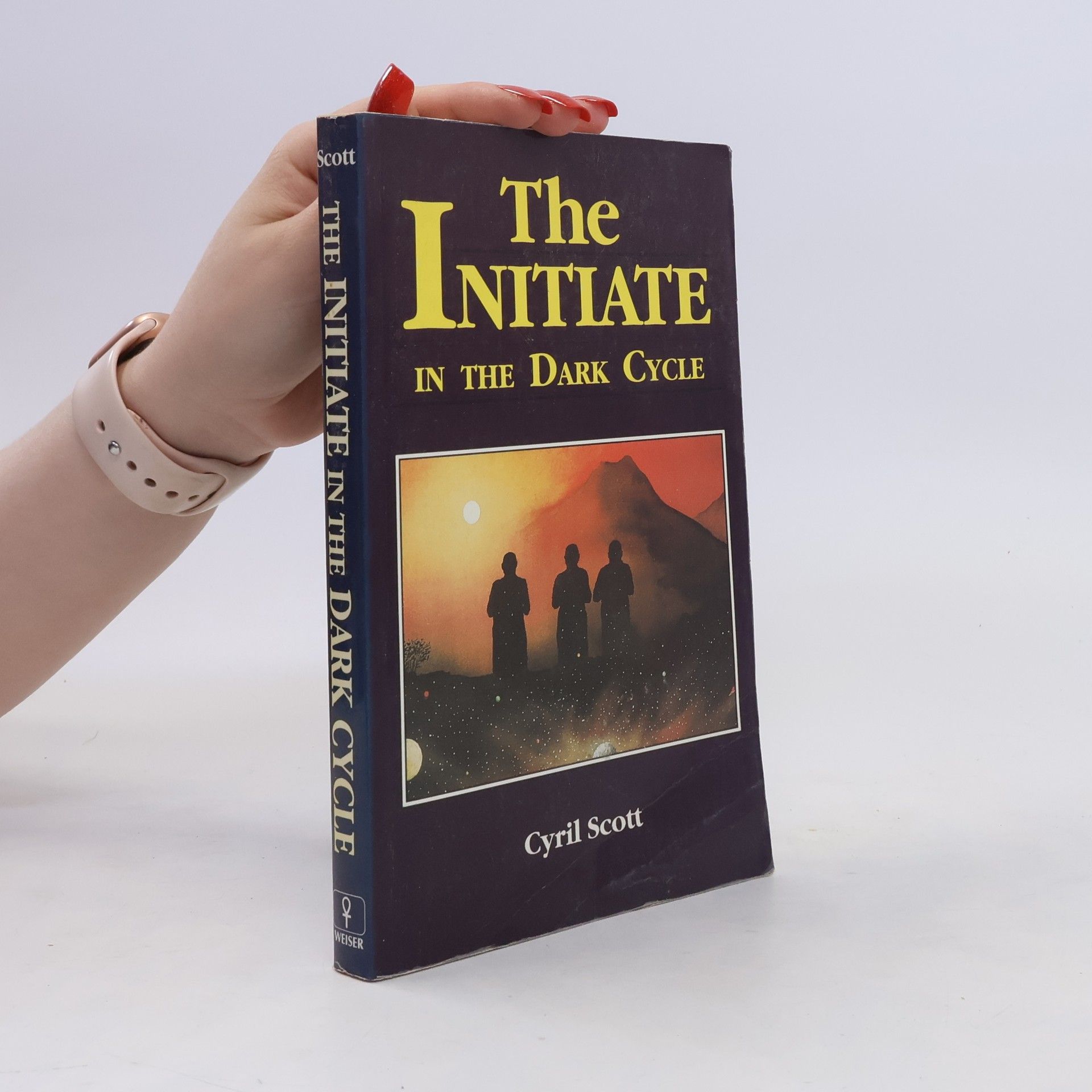

The third volume in the series takes up where The Initiate and The Initiate in the New World leave off, providing more insights into the mysterious Adept known as Justin Moreward Haig. At first, we think that "the dark cycle" relates to the group of students left to their own devices when Justin Moreward Haid disappears for a time. The students meet with the astrologer David Anrias, and become aware of the concepts taught by Krishnamurti and the theosophists. But when Justin Moreward Haid reappears we learn that the dark cycle really indicates a period of destruction and war when Planetary Logos is throwing off and transmuting poisons that create disturbances in the collective astral or emotional body of the human race. In this volume we learn how the group develops, how they relate to their missing teacher, and how they continue their search for spiritual understanding.

Der Eingeweihte - Eindrücke von einer großen Seele von seinem Schüler - bk350; Droemer Knaur Verlag; Hrg. Gerhard Riemann; pocket_book; 1986

Musik

- 275 Seiten

- 10 Lesestunden

Ein kleiner Tagebuchschreiber, von Geburt an hellsichtig, erkennt nicht, dass seine Fähigkeiten eine besondere Gabe darstellen. Er wundert sich, wenn seine kleine Schwester nicht die „Lichter“ (Aura) um andere Menschen sieht. Es ist ihm unbegreiflich, warum er bestraft wird, wenn er von seinen Spielkameraden, den Elfen und Zwergen, berichtet. Dieses Buch ist erfüllt von herzerfrischender Menschlichkeit, übersprudelnder Situationskomik und tiefer Weisheit. Sie werden es lieben, darüber lachen, aus ihm lernen – und es immer wieder zur Hand nehmen, denn so werden die Kinder der Zukunft sein!

This is the veiled history of an Adept who elected to hide his true identity. In this classic work, Scott weaves a wonderful teaching story riddled with profound truths that are as valid today as when this book was first written.