Pravoslav Sovak : krajiny času = landscapes of time

- 220 Seiten

- 8 Lesestunden

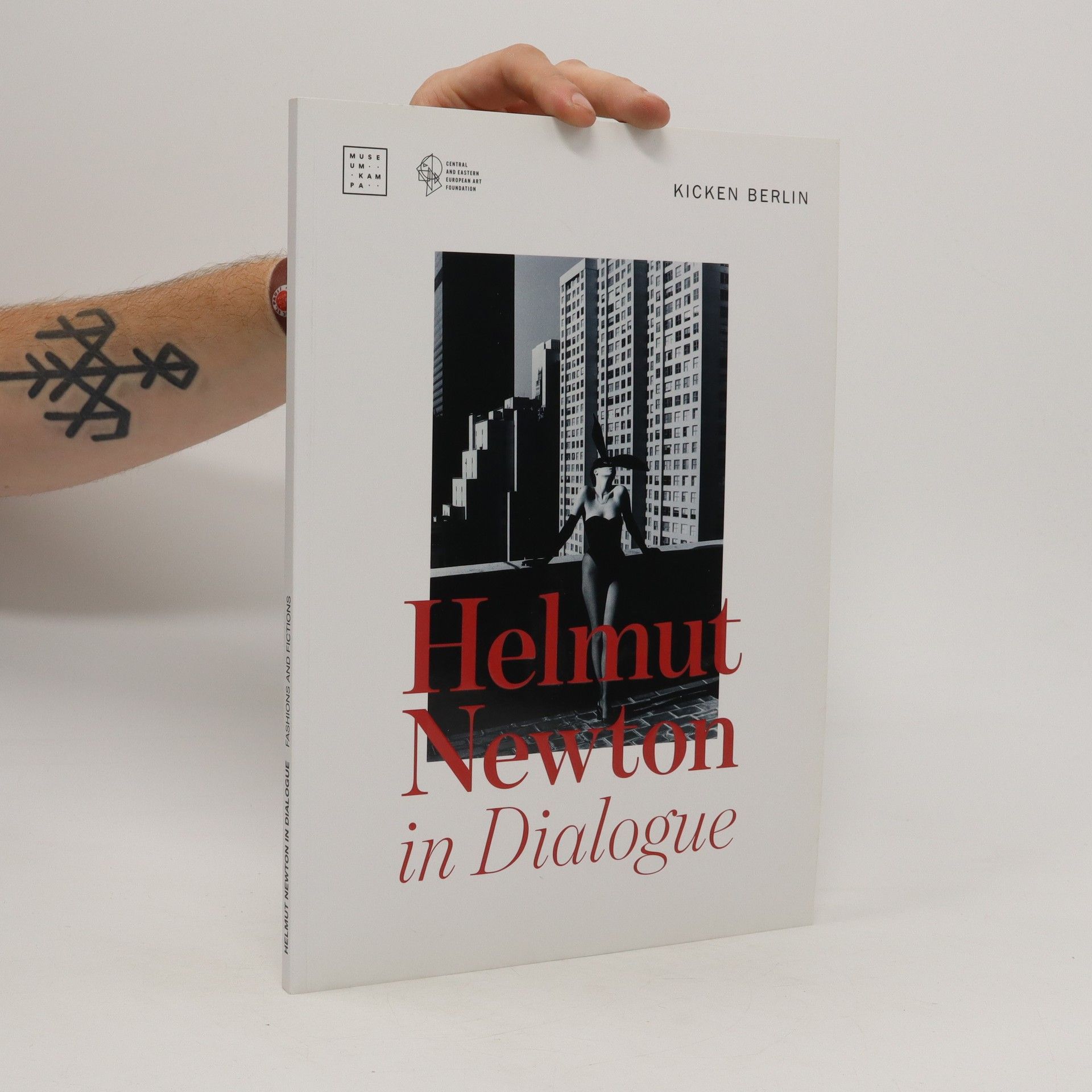

Katalog k výstavě Pravoslav Sovak - Krajiny času. Museum Kampa 24.2. - 27.5.2018

Katalog k výstavě Pravoslav Sovak - Krajiny času. Museum Kampa 24.2. - 27.5.2018

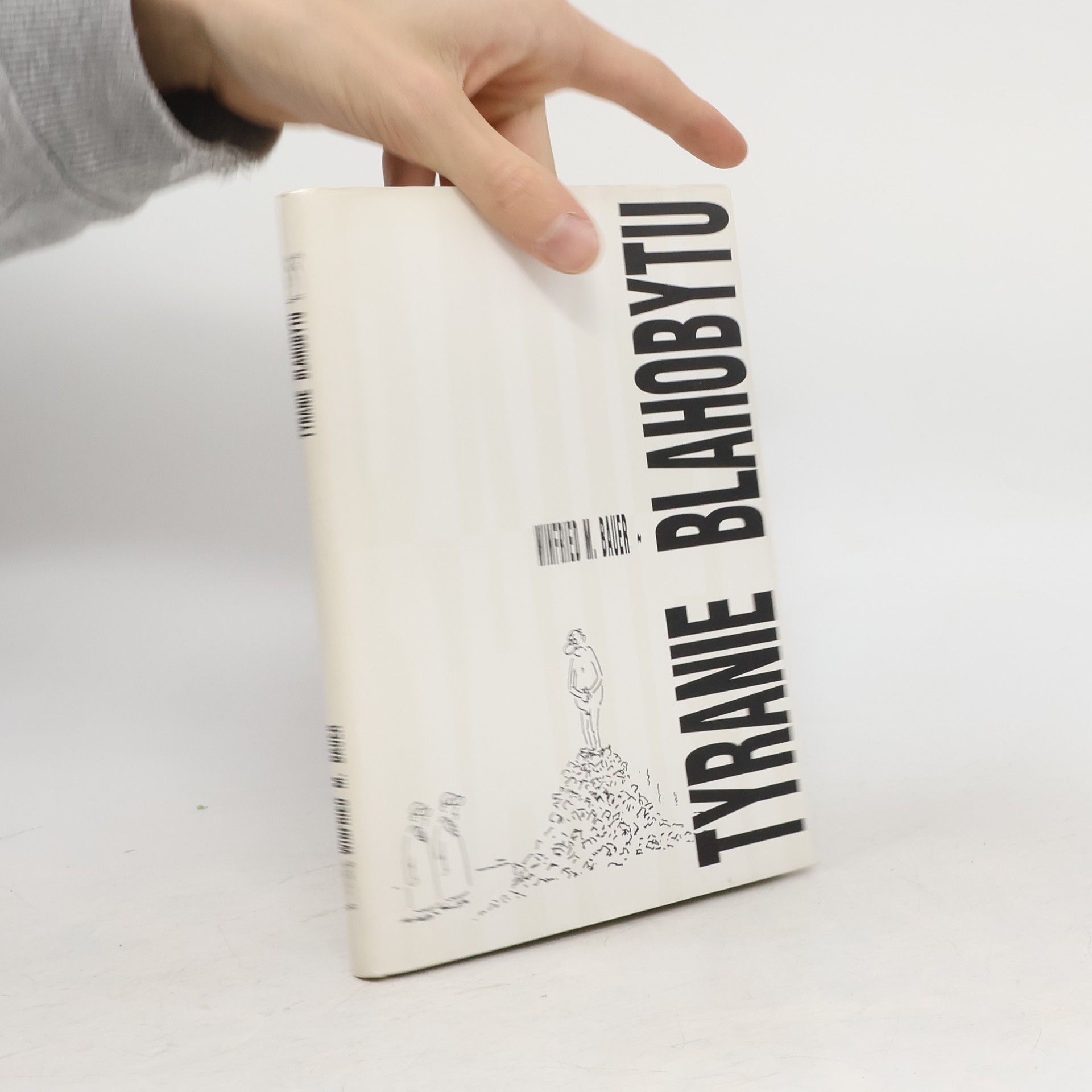

V technokraticky a byrokraticky organizovaném pracovním světě má člověk stále větší problémy prosadit se jako individuální, autonomní a ve své oblasti činnosti aktivní osoba. Byrokracie a státní správa na straně jedné a globálně operující hospodářské organizace na straně druhé nutí k přizpůsobování, v němž člověk přichází o svoji individualitu, nedokáže se identifikovat s prací a nakonec ani se svým soukromým životem. Ztrácí motivaci, jeho výkon klesá a sám tomuto tlaku podléhá, vnitřně se vzdává. V popředí moderní společnosti stojí dnes především rozmnožování blahobytu bez ohledu na všeobecné blaho a životy příštích generací …

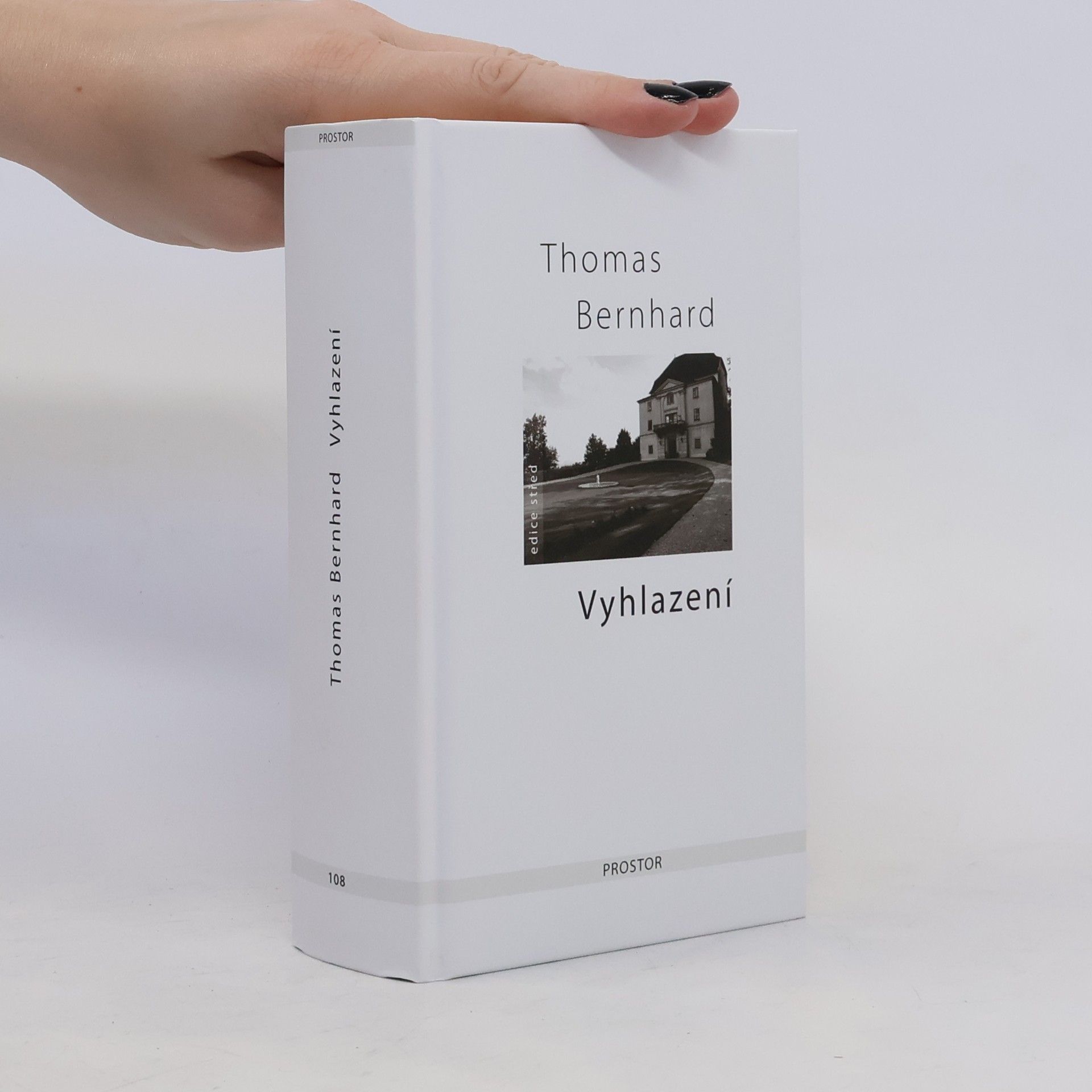

Román Vyhlazení (Auslöschung, 1986) představuje poslední a vrcholný autorův příspěvek světové literatuře. Rozvíjí zde a k dokonalosti přivádí všechny motivy a prostředky, které prostupují jeho tvorbu odpočátku: kritika všeho a všech – zejména rakouského státu a společnosti – jako umění literární nadsázky, všudypřítomná tragikomika, sarkasmus, sebeironie a bytostně hudební rytmus vyprávění.

Výbor miniatur, glos, výstižných črt i krátkých povídek z let 1899–1920 tohoto významného švýcarského autora představuje vhled do jeho tvorby nejvlastnější: v psaní krátkých próz byl Robert Walser jedinečný a neopakovatelný, v mnohém překonávají jeho vlastní romány.

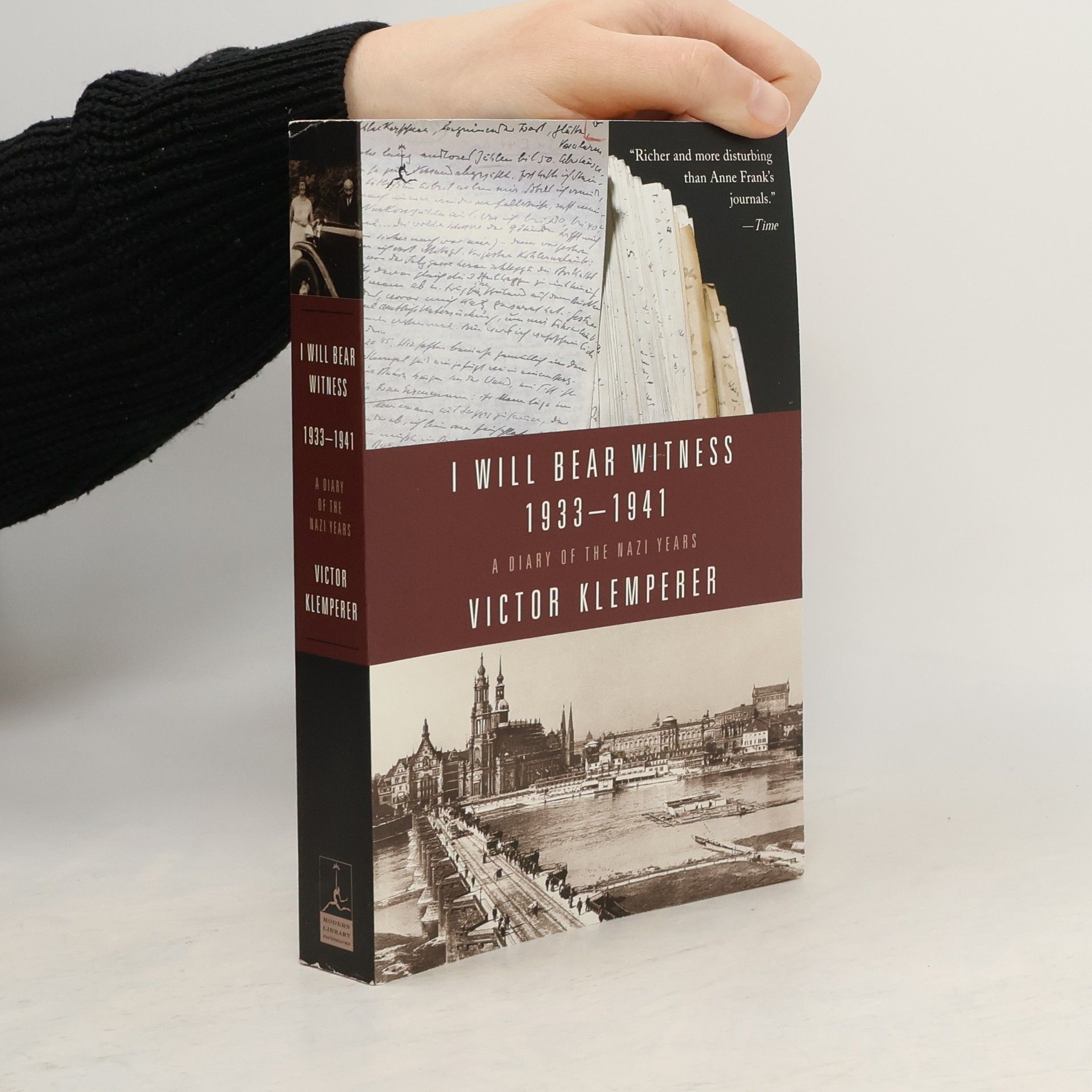

The publication of Victor Klemperer's secret diaries reveals an extraordinary account of daily life during the Nazi period. Described as the best-written and most evocative record of the Third Reich, it combines literary merit with a stark portrayal of the horrors of the era. A Dresden Jew and World War I veteran, Klemperer recognized the dangers posed by Hitler as early as 1933. His clandestine diaries vividly document the experiences of everyday life under Nazi rule, focusing on the thoughts and actions of ordinary Germans, such as the greengrocer and the fishmonger, who share their perspectives on the war's progress. Klemperer, a brilliant historian, struggles to complete his work on eighteenth-century France while witnessing the tightening grip of the regime. He faces the loss of his professorship, his possessions, and ultimately his home, forced into a Jews' House—the last step before the camps. Despite the risks of keeping a diary, he feels compelled to record the unfolding events, stating, "This is my heroics. I want to bear witness, precise witness, until the very end." Klemperer emphasizes the significance of documenting the everyday life of tyranny, asserting that "a thousand mosquito bites are worse than a blow on the head." This volume covers the years from 1933 to 1941, with a second volume planned for 1999.

Rudolf, der Erzähler dieses 1982 erschienenen Buches, bereitet seit einem Jahrzehnt mit leidenschaftlichem Ernst eine größere wissenschaftliche Arbeit über seinen Lieblingskomponisten Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy vor. Nachdem er zuerst durch den Besuch seiner Schwester und dann, nach ihrem Weggang, durch die quälende Furcht, sie könnte wieder zurückkommen, am Schreiben des ersten Satzes seiner Studie gehindert wird, quält ihn die »Hölle des Alleinseins«. Deshalb packt er die Koffer, nimmt nur die wichtigsten seiner Schriftstücke mit, um in Palma seine Arbeit zu realisieren. In einem dortigen Cafe erinnert er sich an eine junge Frau, die ihn bei seinem letzten Palma-Aufenthalt vor eineinhalb Jahren angesprochen hatte. Sie war verzweifelt, ihr Mann hatte sich nachts vom Balkon des Hotels Paris gestürzt. Auf dem Friedhof von Palma, in einem der sieben Stock hohen Betonbestattungskästen, ist er beerdigt worden. Noch jetzt, eineinhalb Jahre danach, sieht er das verzweifelte Gesicht der Frau. Nun hat er eine Reihe von ersten Sätzen für seine Arbeit im Ohr, aber auch das Unglück der jungen Frau. Er nimmt ein Taxi, fährt zum Friedhof und findet an der Tafel neben dem Namen des Mannes nun auch den Namen der Frau: suicido – erfährt er.

Der Geheime Zauberrat Beelzebub Irrwitzer und seine Tante, die Geldhexe Tyrannja Vamperl, haben ein großes Problem: Das Jahr neigt sich dem Ende zu und beide haben ihr Soll an bösen Taten noch lange nicht erfüllt. Daran sind nur Kater Maurizio und der Rabe Jakob schuld, die ihnen vom Hohen Rat der Tiere auf den Hals gehetzt wurden. Doch mit einem besonders raffinierten Plan könnte es den beiden Zauberern noch gelingen, den Rückstand an bösen Taten aufzuarbeiten. Maurizio und Jakob entdecken die bösen Absichten, aber können sie diese auch verhindern? Ein Wettlauf mit der Zeit beginnt.

Ein Landarzt aus der Steiermark nimmt seinen Sohn auf Visite mit, einen Tag lang. Fälle präsentieren sich, wie eine Landpraxis sie bringt, Fälle, wie sich zeigt, die jenseits medizinischer Möglichkeiten erst beginnen.