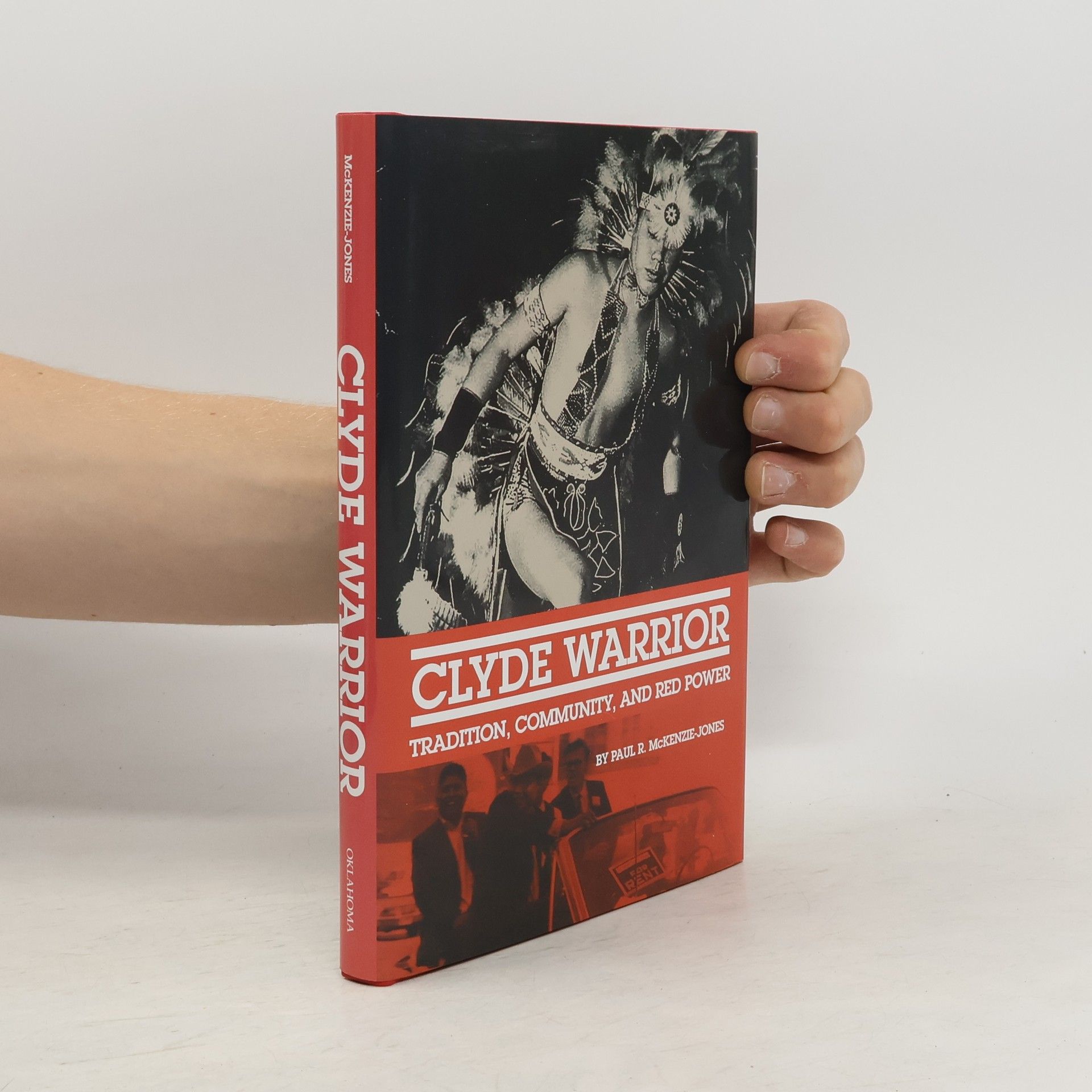

The phrase Red Power, coined by Clyde Warrior in the 1960s, introduced militant rhetoric into American Indian activism. In this first-ever biography of Warrior, historian Paul R. McKenzie-Jones portrays him as the architect of the Red Power movement, highlighting his significance in the fight for Indian rights. This movement emerged in response to centuries of federal oppression, encompassing grassroots organizations advocating for treaty rights, tribal sovereignty, self-determination, and cultural preservation. As a cofounder of the National Indian Youth Council, Warrior became a prominent spokesperson, leading a cultural and political reawakening in Indian Country through ultranationalistic rhetoric and direct-action protests. McKenzie-Jones utilizes interviews with Warrior’s associates to explore the complexities of community, tradition, culture, and tribal identity that influenced his activism. Despite his untimely death at twenty-nine overshadowing his legacy, McKenzie-Jones reveals previously unchronicled connections between Red Power and Black Power, illustrating their simultaneous emergence as urgent calls for social change. Warrior, descended from hereditary chiefs, was deeply rooted in Ponca history and language, and his experiences shaped his intertribal approach to Indian affairs. This biography examines how Warrior’s dedication to culture and community laid the foundation for his vision of Red Power.

Neue Richtungen in den Indianerstudien Reihe

Diese Reihe beleuchtet die vielfältige Welt der amerikanischen Ureinwohner und hebt ihre aktive Teilnahme an breiteren gesellschaftlichen Strömungen sowie ihre anhaltende Kreativität hervor. Die Bücher enthüllen die Stärke ihrer Ausdauer und ständigen Erneuerung im Laufe der Geschichte bis in die Gegenwart. Mit einem Fokus auf einen innovativen und interdisziplinären Ansatz trägt sie zu einem tieferen Verständnis des indigenen Amerikas über spezialisierte akademische Kreise hinaus bei.

Focusing on the relationship between ancient Anaasází structures and contemporary Native nations, this book explores how archaeological findings alone may not capture the full narrative of the Southwest's history. Historian Robert McPherson advocates for integrating archaeological insights with the oral traditions of the Navajo, Ute, Paiute, and Hopi peoples, proposing that this combined approach provides a richer understanding of the region's past and its ongoing cultural significance.

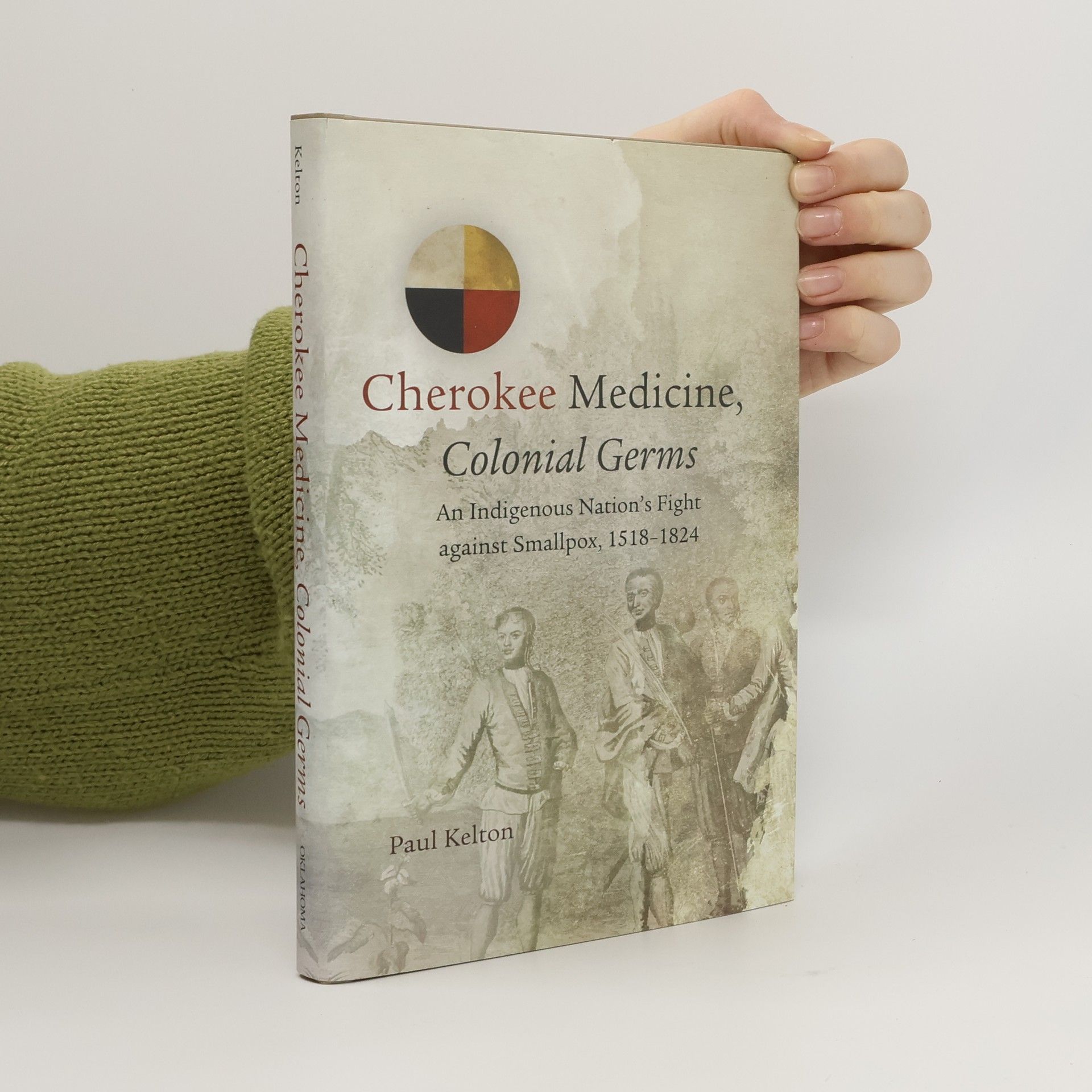

New Directions in Native American Studies - 11: Cherokee Medicine, Colonial Germs

An Indigenous Nation’s Fight against Smallpox, 1518–1824

- 296 Seiten

- 11 Lesestunden

How smallpox, or Variola, devastated populations during European colonization is a well-known narrative. Historian Paul Kelton challenges the “virgin soil thesis,” which attributes Native American suffering to their lack of immunities and ineffective healers. Instead, he emphasizes that the root cause of indigenous depopulation was colonialism, not disease. Kelton's account begins with the period from 1518 to the mid-seventeenth century, when limited interactions with Europeans did not significantly alter Cherokee lives. By the 1690s, English slave raids led to a devastating smallpox epidemic among the Cherokees. Throughout the eighteenth century, they effectively responded to epidemics using their own medicinal practices, even as they faced severe violence from British forces during the Anglo-Cherokee War and American militias in the Revolutionary War. The Cherokee population suffered more from warfare than from smallpox, rebounding in the nineteenth century. They embraced vaccination while maintaining their traditional medical practices. This nuanced history highlights the lived experiences of the Cherokees, challenging the simplistic narratives perpetuated by Europeans and their descendants, and revealing how these stories have obscured the complexities of colonialism.